Skip to content

Current ExhibitionA Very Still Life – Tsuki Garbian

Feb 05, 2026Mar 07, 2026

-

Spanga Home | oil on canvas110X90 cm, 2025

-

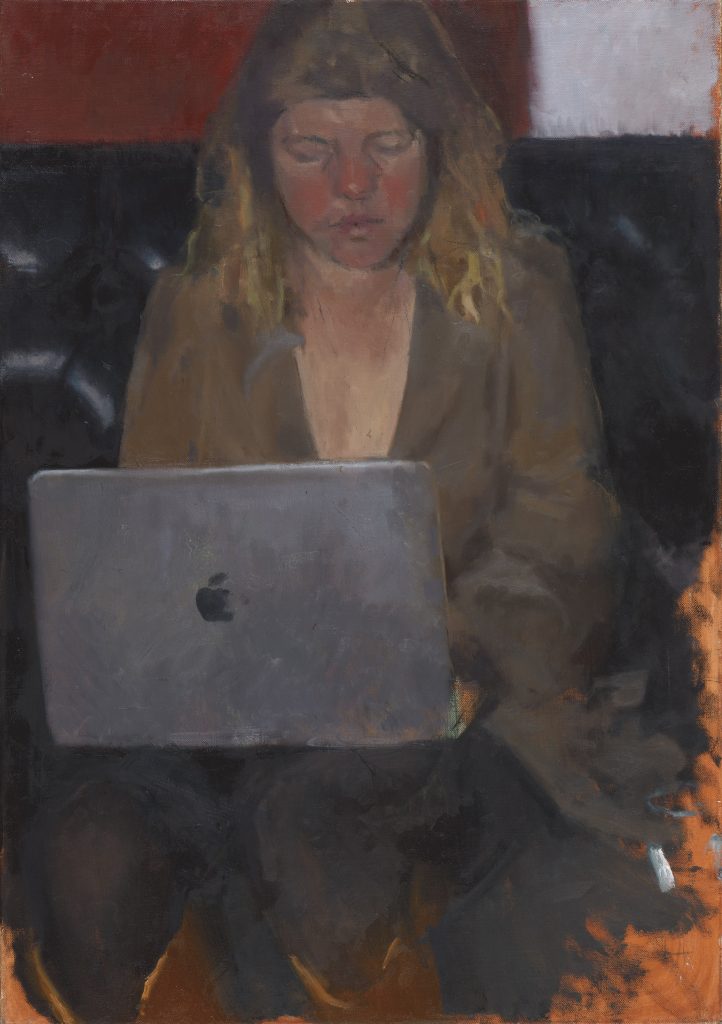

Leila | Oil on canvas60X85 cm, 2025

-

Leila in the studio | oil on canvas100X80 cm, 2025

-

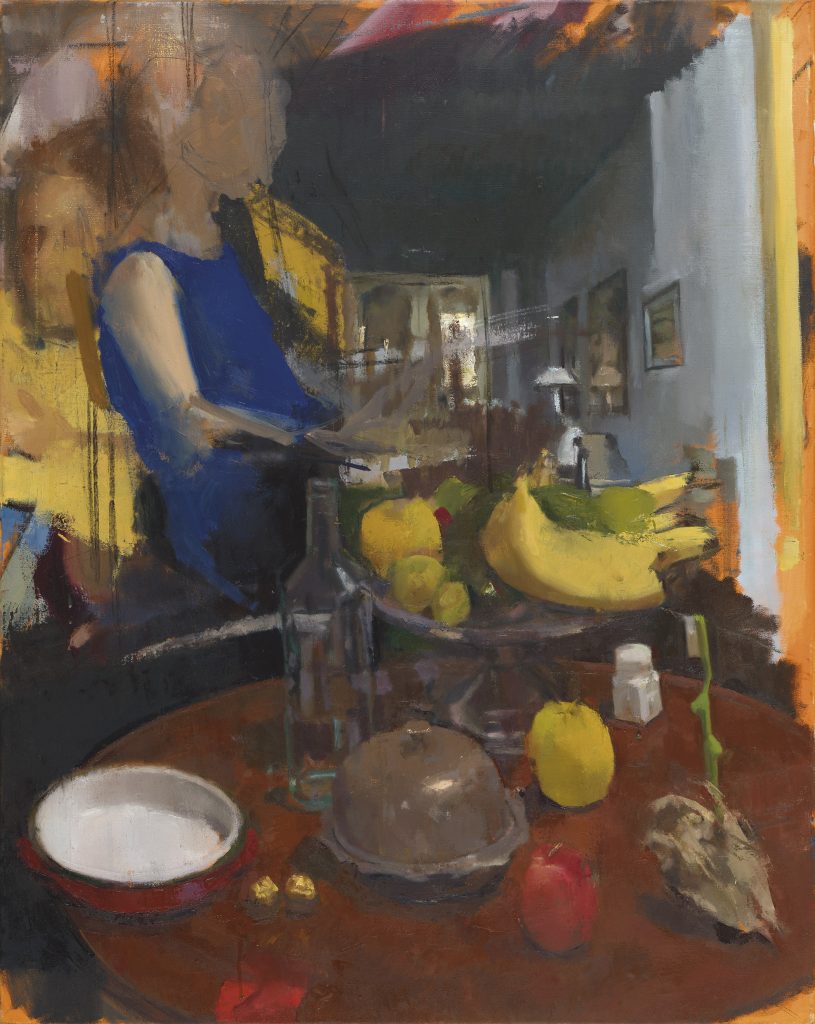

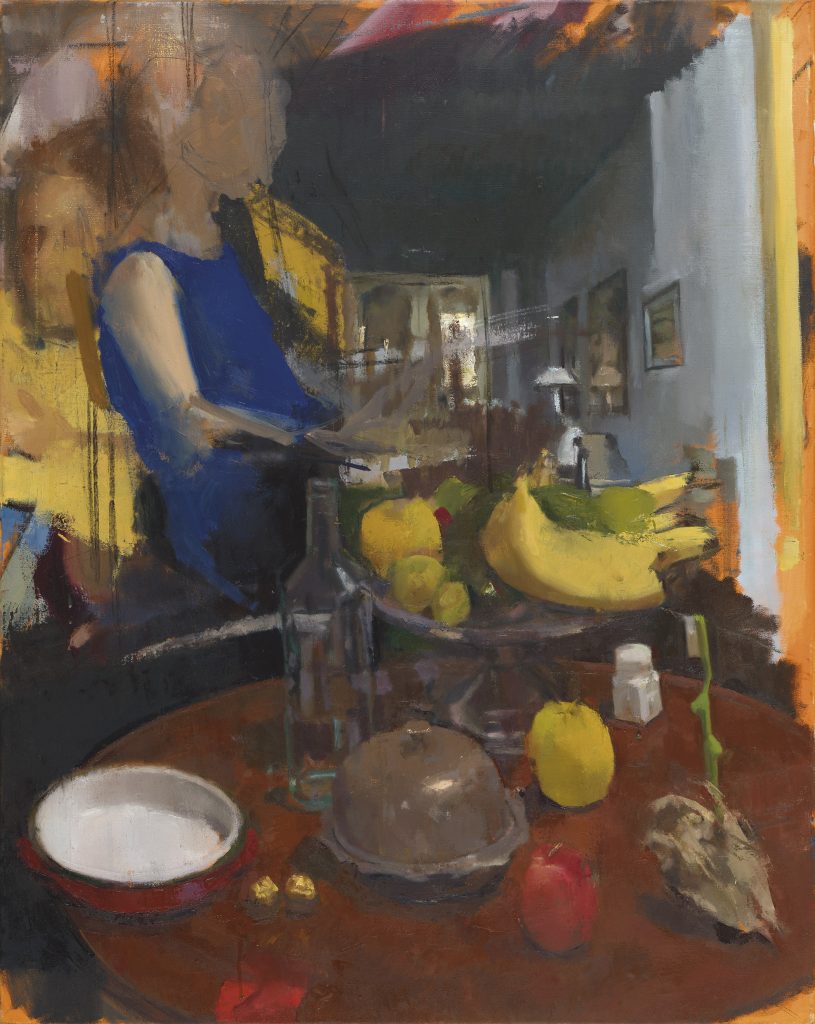

Round Table | oil on canvas100X80 cm, 2026

-

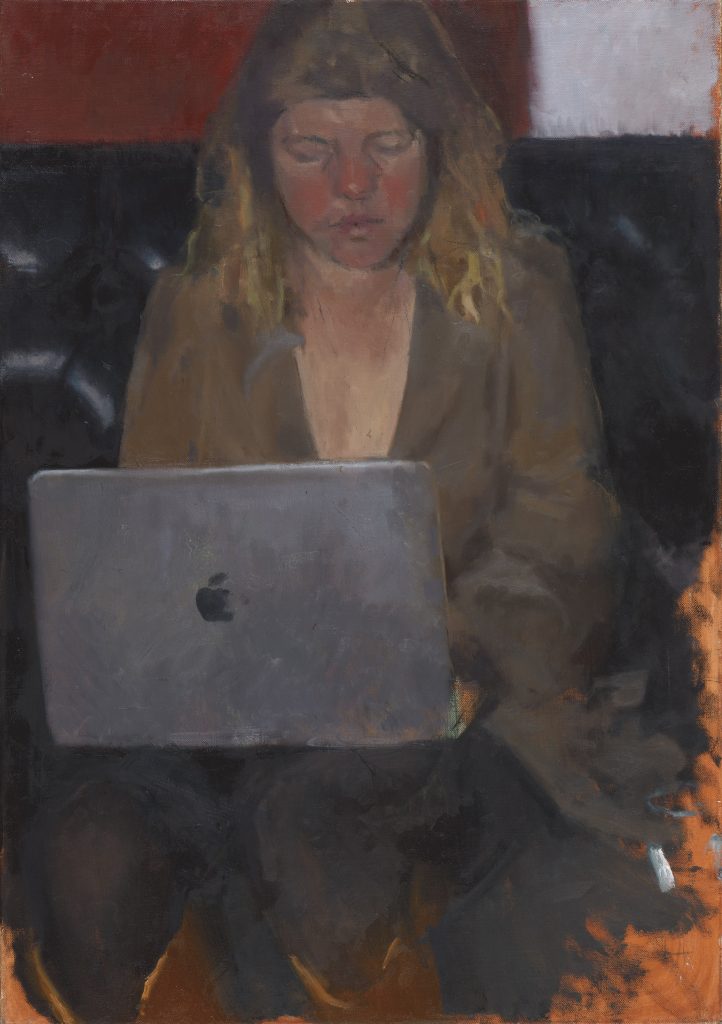

Kayla | oil on canvas85X60 cm, 2026

-

Leila | oil on canvas85X60 cm, 2026

-

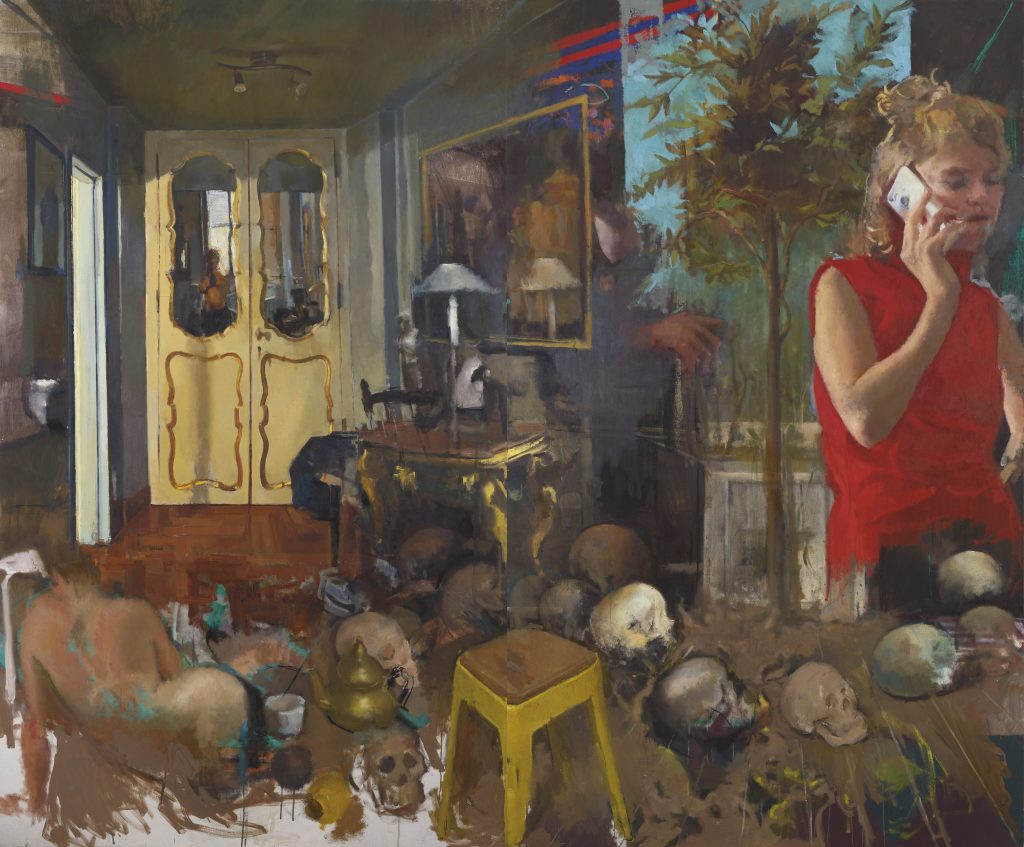

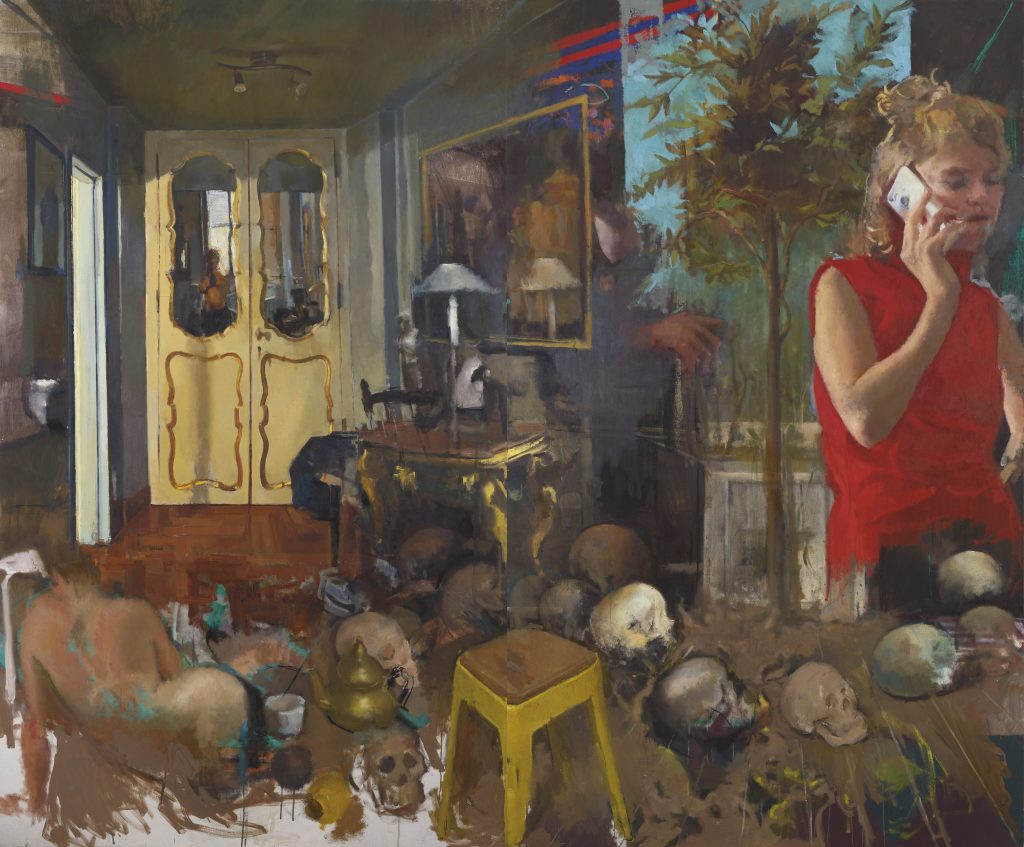

Untitled | Diptych, oil on canvas mounted on wood200X240 cm, 2025-26

-

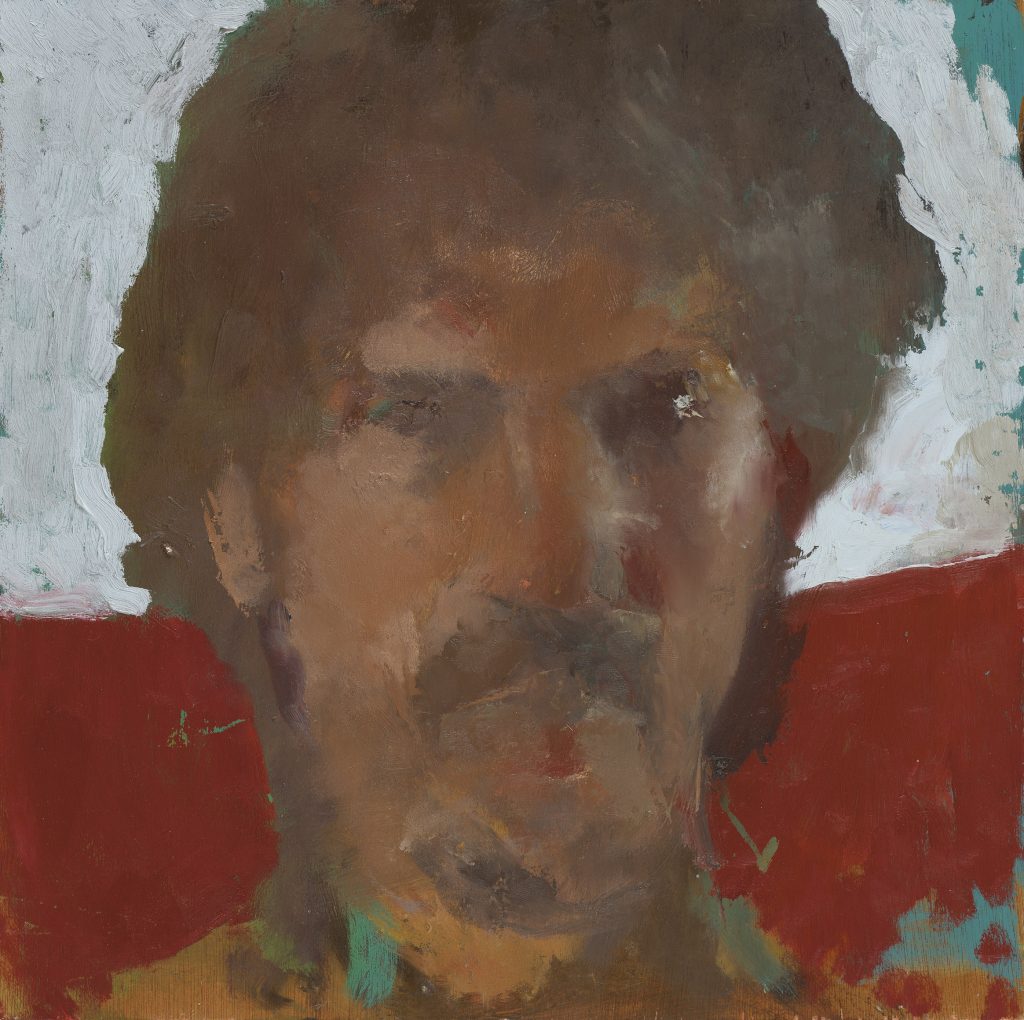

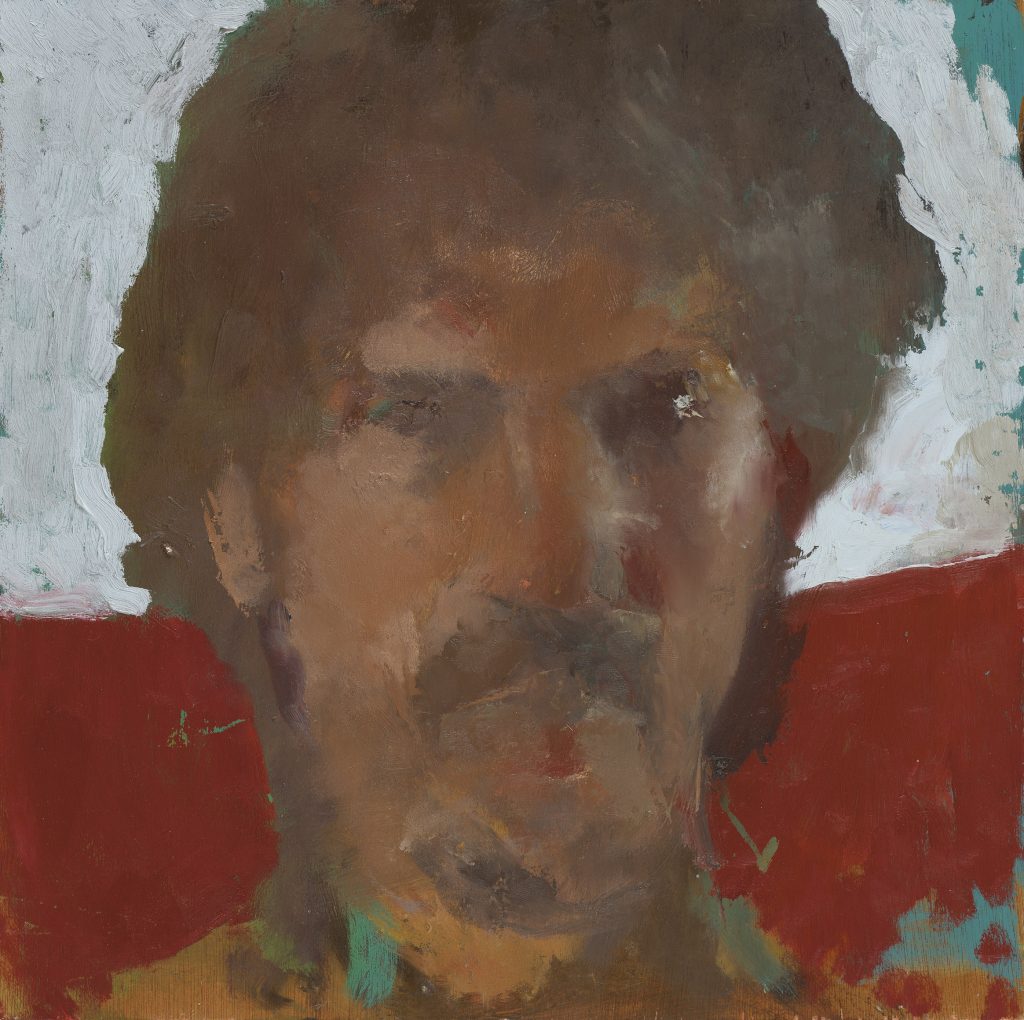

Self portrait | Oil on plywood30X30 cm, 2025

-

Still Life | oil on canvas mounted on wood61X95 cm, 2026

-

Still Life | oil on canvas mounted on wood42.6X22.8 cm, 2025

-

Still Life | oil on canvas mounted on wood22.6X32.5 cm, 2025

-

Composition with Moka Pot | oil on canvas mounted on woods19.7X49.8 cm, 2025

-

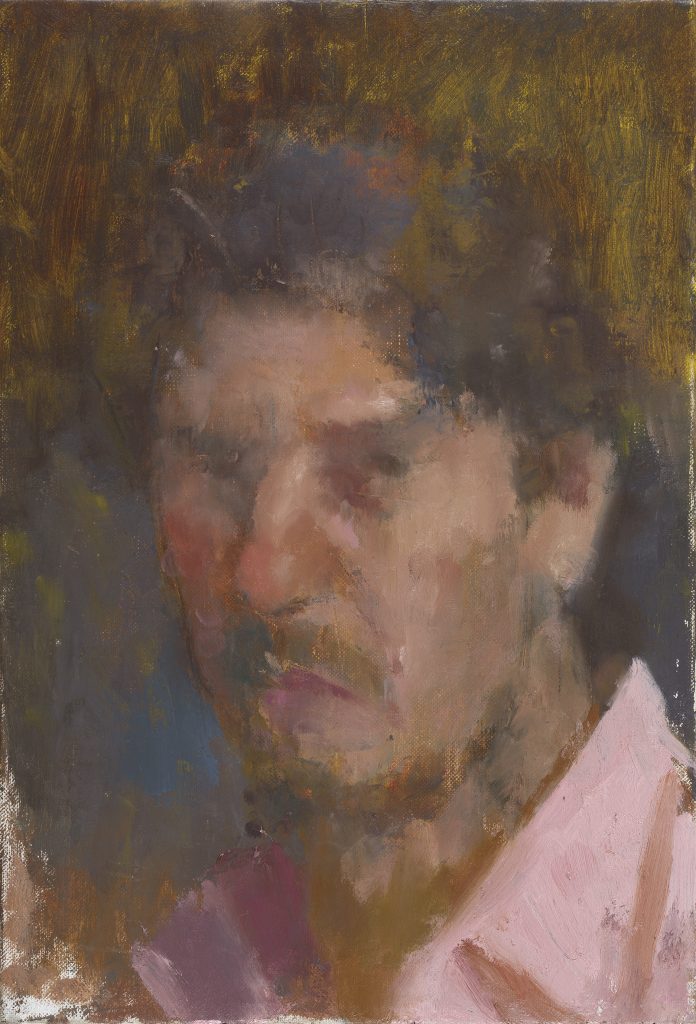

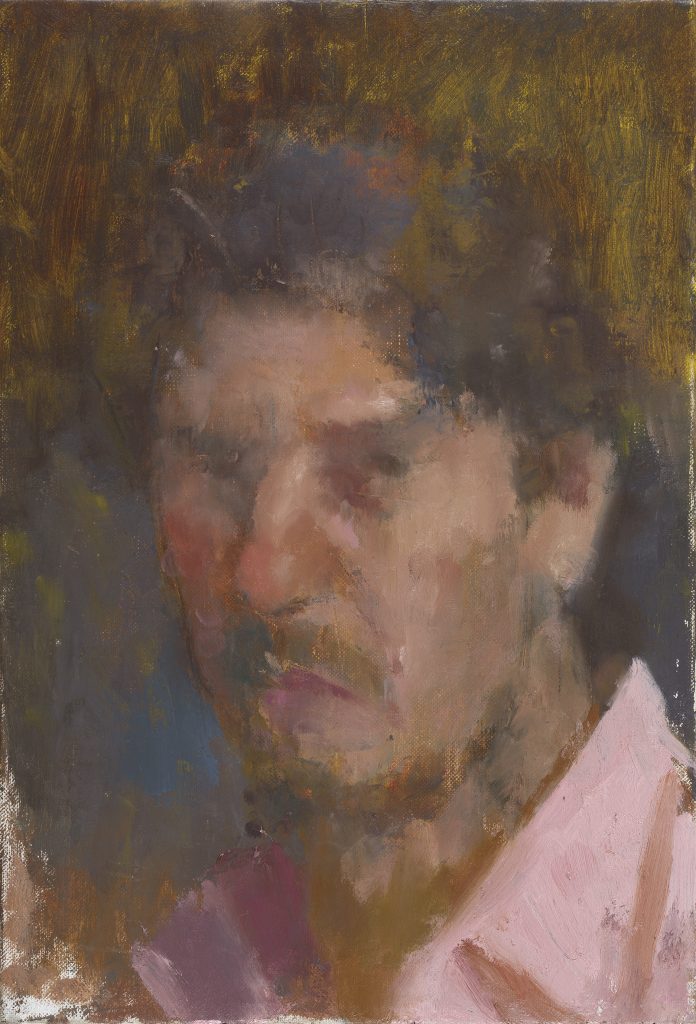

Self-portrait with a pink collar | oil on canvas mounted on wood33.4X22.8 cm,2025

-

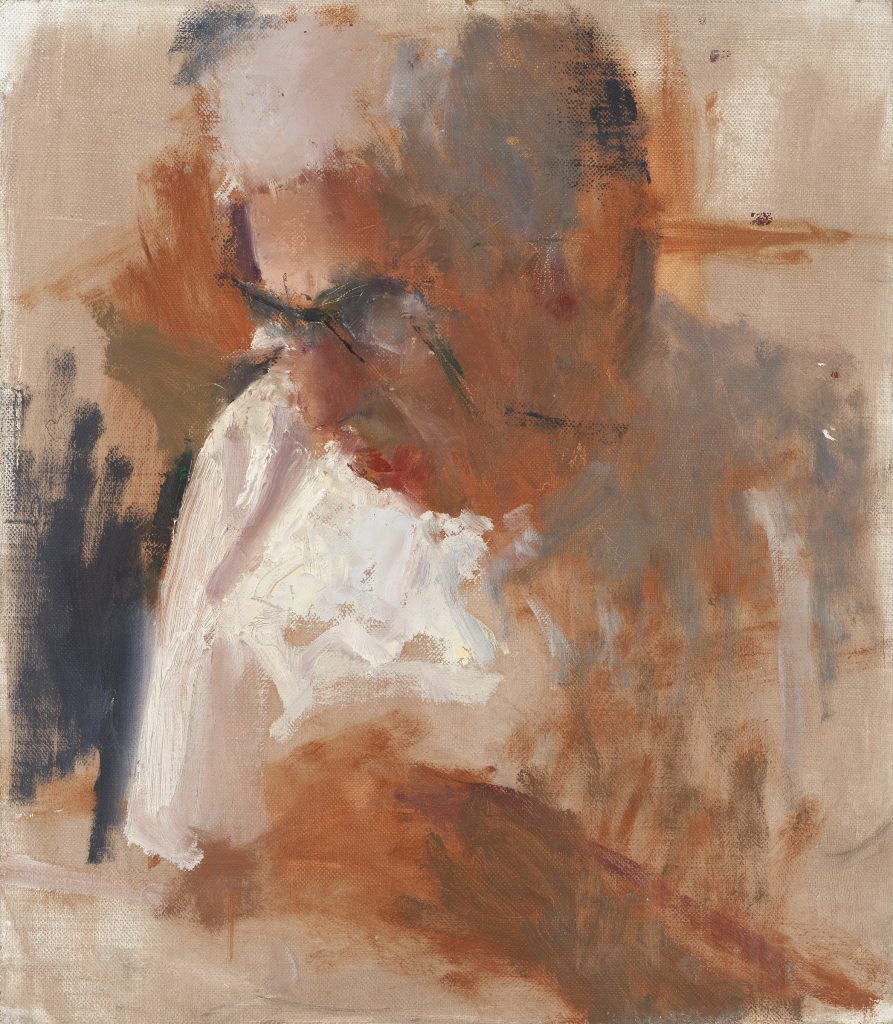

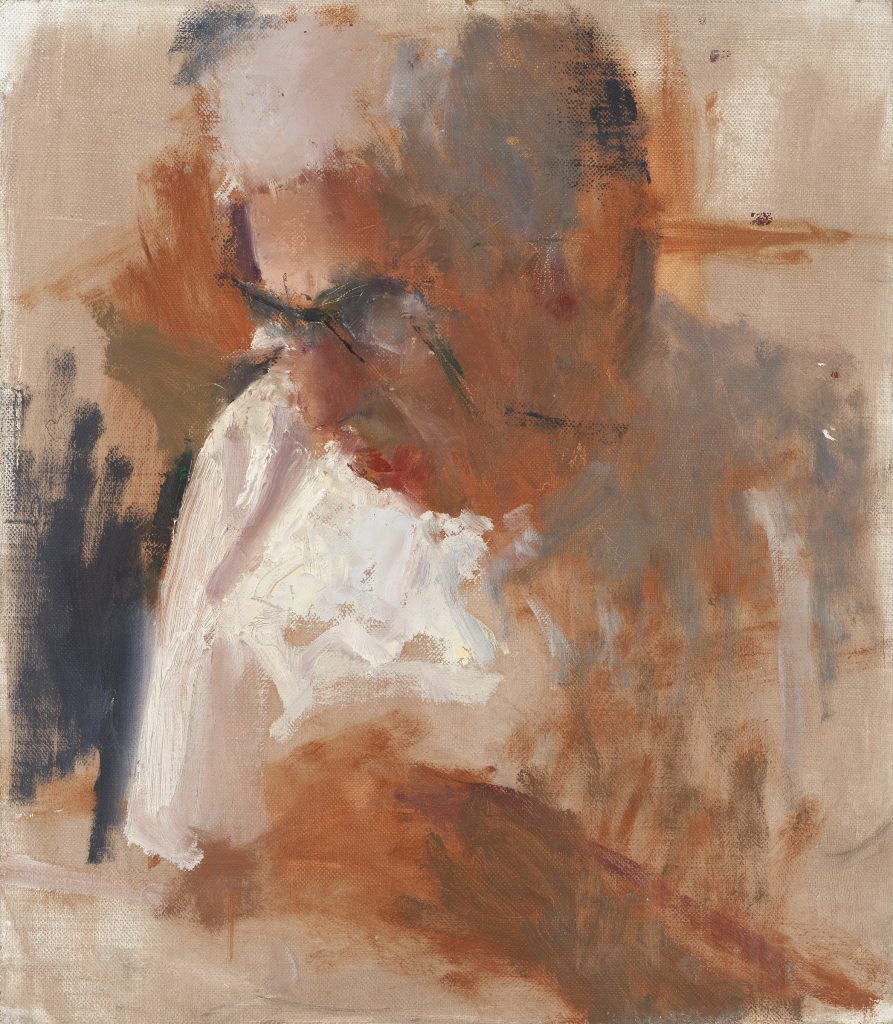

Portrait of my Father, oil on canvas mounted on wood, 42.5X37 cm

-

Still Life, oil on canvas100X100 cm, 2025

-

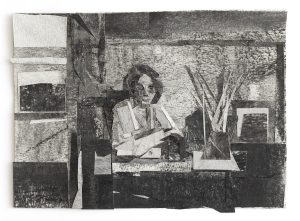

Self portrait in the studio | oil on canvas100X80 cm, 2025

-

Gal | oil on canvas mounted on wood39.4X24 cm, 2025

-

Layla | oil on canvas mounted on wood29.3X24.6 cm

All Exhibitions

2025

In Place - Uri Blayer

Nov 27, 2025Dec 27, 2025

Thin Air Hangs over the Home - Noga Paz & Tigist Yoseph Ron

Oct 23, 2025Nov 22, 2025

Circling Between Darkness and Light - Noa Shay

Sep 02, 2025Oct 18, 2025

At the violet hour - Boaz Levental

Jul 10, 2025Aug 09, 2025

Inner Echo - Silvia Bar - Am

May 29, 2025Jul 05, 2025

Meir Appelfeld - On the Threshold

Apr 24, 2025May 25, 2025

Alma Gershuni - Sight of the Eyes

Mar 18, 2025

Ran Tenenbaum - Solar Plexus

Feb 11, 2025Mar 15, 2025

Zvi Lachman - Crossing Line

Jan 08, 2025

2024

Asya Lukin - Direct Glance

Dec 05, 2024Jan 04, 2025

Simon Adjiashvili - Forgotten Room

Oct 30, 2024Nov 30, 2024

Matan Ben Cnaan - Hadrian's Helmet

Sep 04, 2024

Dana Ben Nun - FACETS

Jul 30, 2024

Anne Ben Or - Grasping the Edge of Time

Jun 16, 2024

Osnat Ben Dov - Nur

May 15, 2024Jun 15, 2024

David Nipo - Birds Sang

Apr 04, 2024May 11, 2024

2023

Sam Rachamin - Easy on the Eyes

Sep 02, 2023

Yuval Yosifov - Tonal Stories

Jul 01, 2023Aug 01, 2023

Tamar Beit On - Sculptures, Silvia Bar-Am - A City Wreathed in Light

May 29, 2023

Meir Appelfeld - Interiors

Apr 13, 2023May 20, 2023

Simon Adjiashvili - Muted Horizon

Mar 07, 2023

Rotem Amizur - The Flat Islands

Jan 30, 2023

2022

Uri Blayer - Another Dimension

Dec 24, 2022Jan 28, 2023

Beverly Barkat - Galloping

Nov 12, 2022

Yehuda Armoni - Here, Green in its full wholeness is gaping wide

Sep 01, 2022

Boaz Levental - Inside Out

Aug 20, 2022

Anne Ben Or - The Return of the Ornament

Jun 16, 2025Jul 16, 2022

Hadar Gad - Intolerable Beauty

Apr 07, 2022

Eran Webber - Sanguine

Feb 28, 2025Apr 02, 2025

Sam Drukker, Alex Kremer - The Way of the Gaze

May 12, 2022Jun 11, 2022

David Nipo - Over time, a Roman fresco, seems like a poem by Avigdor Hameiri

Jan 22, 2022

Adam Cohn - Between Still and Life

Oct 03, 2022Nov 12, 2022

2021

Anna k., Twenty painters, ten years, one model

Dec 23, 2021Jan 22, 2022

Osnat Ben Dov - Until the Heart Brims with Wisdom

Nov 06, 2021

Meir Applefeld - Arcadia

Oct 02, 2021Nov 06, 2021

Drawings - Group Exhibition

Jul 31, 2021Sep 30, 2021

Simon Adjiashvili - Next to the Shadow

Jun 27, 2021

Adam Cohn - Street Portraits

May 21, 2021

Deborah Sebaoun - smiles from reason

Apr 05, 2021

2020

Rotem Amizur - Rubik's Cube

Dec 15, 2020

Roni Taharlev - Berlin-Jaffa

Dec 03, 2020

Yehuda Armoni - 70% Water

Oct 29, 2020

Anne Ben Or - Reflexion Time

Aug 13, 2020Sep 25, 2020

Sam Rachamin - Catching the Light

Jul 02, 2020Aug 08, 2020

Adam Cohn - In the Wake of Reality

Mar 19, 2020Jun 27, 2020

Debbie Margalit - Ayala and Gertrude in Square

Jan 09, 2020Feb 09, 2020

2019

Michal Sheizaf - Pose

Dec 05, 2019Jan 10, 2020

Yedidya Hershberg - At The Still Point, There The Dance Is

Oct 24, 2019

Simon Adjiashvili - Distant Night

Sep 05, 2019

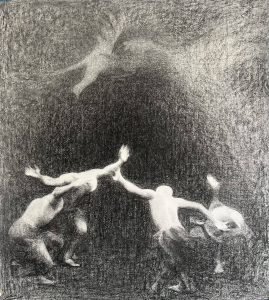

Noa Shay - Dance of the Happy Shades

Jul 11, 2019Aug 31, 2019

Roni Taharlev - Portraits

May 30, 2019Jul 06, 2019

Rotem Amizur - Rock, Paper, Scissors

Mar 07, 2019Apr 06, 2019

Ran Tenenbaum - Illuminated

Jan 24, 2019Mar 02, 2019

Meir Appelfeld - Paintings

Apr 11, 2019May 25, 2019

2018

Yael Scalia - Palimpsest

Dec 21, 2018

Maia Zer - Listening to Insects

Nov 22, 2018Dec 22, 2018

Anne Ben-Or - State of Mind

Oct 11, 2018

Group Summer Exhibition

Aug 09, 2018Oct 06, 2018

Alex Kremer - SEISMOGRAPH

May 31, 2018

E.M Saniga - Color of Time

Jun 28, 2018

Uri Blayer - Landscapes and Coastlines

May 03, 2018May 26, 2018

Jordan Wolfson - Thicket

Mar 21, 2018Apr 21, 2018

Yehuda Armoni - Lingering Gaze

Feb 15, 2018Mar 15, 2018

Simon Adjiashvili - Symmetry

Jan 04, 2018Feb 10, 2018

2017

Iddo Markus - Gossip

Nov 23, 2017Dec 30, 2017

Leonid Balaklav - Paintings

Oct 19, 2017

Hadar Gad - Red

Aug 26, 2017

Maia Zer - Nine Lives

Jul 06, 2017

Yedidia Hershberg - More Image Than a Shade

May 25, 2017Jun 25, 2017

Meir Appelfeld - Paintings

Apr 20, 2017May 20, 2017

Alex Kremer - BADOGOODOG

Mar 16, 2017Apr 16, 2017

Roni Taharlev-The Land Where The Lemon Trees Bloom

Jan 26, 2017Feb 26, 2017

2016

Anne Ben Or - Secret Games

Dec 15, 2016Jan 15, 2017

Simon Adjiashvili - Days

Nov 03, 2016Dec 10, 2016

Uri Blayer - Landscapes and Portraits

Sep 01, 2016Oct 25, 2016

Meir Applefeld - Pastels

Mar 17, 2016

Iddo Markus - Glitch

Mar 17, 2016

genius loci

Jan 28, 2016Mar 10, 2016

2015

Alex Kremer - Walking Distance

Dec 10, 2015Jan 23, 2016

Yael Scalia - Delight in All Seasons

Oct 22, 2015Nov 22, 2015

Not in One Day / Group Exhibition

Sep 03, 2015Oct 17, 2015

Jordan Wolfson - New Work

May 28, 2015Jun 27, 2015

Anne Ben Or - Defiance

Meir Appelfeld-Paintings

Apr 30, 2015

Ken Kewley - Bottles, Trees, and Things: New Invented Still Lifes

Mar 09, 2015Apr 18, 2015

Ilya Gefter - The City: Paintings And Ink Washes

Jan 29, 2015Mar 09, 2015

2014

Simon Adjiashvili - One City, One Summer

Dec 11, 2014

Yonatan Pelles - Paintings

Nov 13, 2014Dec 13, 2014

Ludwig Blum&Uri Blayer - Painters in the Desert

Sep 11, 2014

Shalom Flash - Vanishing Scenes

Jun 26, 2014Jul 31, 2014

Meir Applefeld - ''Moon Grove''

May 15, 2014Jun 17, 2014

Tsuki Garbian - Life-likeness

Apr 03, 2014May 03, 2014

Uri Blayer - Under Northern Skies

Feb 13, 2014Mar 22, 2014

Raoul Middleman - ''Figures and Portraits''

Jan 10, 2014Feb 15, 2014

2013

Simon Adjiashvili, Ilya Gefter, Paintings

Dec 12, 2013

JSS' Master Class Exhibition

Nov 18, 2013Dec 01, 2013

Nomi Bruckmann - With This Night With The Dark Cypress With The Pale Light

Jul 11, 2013

Jordan Wolfson - New Work

May 30, 2013Jun 30, 2013

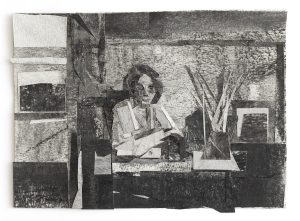

Simon Adjiashvili - Drawings

Apr 08, 2013May 25, 2013

Portraits - Group Exhibition

Feb 28, 2013Apr 06, 2013

Meir Appelfeld - Paintings

Oct 03, 2013Nov 09, 2013

2012

Stuart Shils - What Time Has Not Lost

Dec 29, 2012Feb 23, 2013

Hadar Gad - Four Entered an Orchard

Nov 15, 2012Dec 22, 2012

Masada- Land and Landscape / Uri Blayer

Sep 06, 2012Jul 30, 2012

Ken Kewley - Paintings and collages 2008-2012

Jun 28, 2012Aug 20, 2012

Tirza Freund, ''Suppose a thing''

May 12, 2012Jun 05, 2012

Simon Adjiashvili - Recent Work

Mar 15, 2012May 05, 2012

Meir Appelfeld - Paintings

Jan 12, 2012Mar 03, 2012

2011

Group Drawings Exhibition

Jul 18, 2011Aug 31, 2011

Shalom Flash - Landscapes

Nov 26, 2011Jan 04, 2012

Sangram Majumdar- Selected works 2008-2011

Sep 08, 2011Nov 20, 2011

Jordan Wolfson - Inside and Behind

May 19, 2011Jul 10, 2010

''Close Your Mouth and Say One Word" / Group Exhibition

Mar 31, 2011May 10, 2011

Hadar Gad - Not the same

Feb 26, 2011Mar 26, 2011

2010

Ken Kewley Painting and collages 2000-2010

Dec 30, 2010Feb 20, 2011

Sharon Etgar - Oils and Papers 2009-10

Nov 25, 2010Dec 25, 2010

Meir Appelfeld - Painting

Oct 14, 2010Nov 20, 2010

Gallery Collection

Sep 01, 2010

Sigal Tsabari-Reflection from Within

Jul 01, 2010Aug 15, 2012

Simon AdjIiashvili-Recent Works

Apr 22, 2010Jun 25, 2010

Stuart Shils,1986 to present

Mar 04, 2010Mar 17, 2010

Ben Tritt ,Book 4: The Flood

Dec 24, 2009Feb 01, 2010

2009

Yael Scalia Recent work

Nov 05, 2009Dec 05, 2009

Meir Appelfeld Jerusalem-Cabri

Jun 11, 2009Sep 01, 2009

''The Unbelievable Is right here''

Sep 10, 2009Oct 31, 2009

Jordan Wolfson -States of Being

Mar 05, 2009Jun 01, 2009

Michael Ajerman / The good, the bad and the ugly

Jan 10, 2009Feb 25, 2009

2008

Mitch Becker - Counterpart

Nov 20, 2008Jan 01, 2009

Meir Appelfeld- Flowers

Sep 13, 2008Nov 10, 2008

Group Exhibition

Jul 03, 2008Sep 05, 2008

Enquire

Enquire